One of the most difficult things about studying tea is sitting seiza. As I am getting older, it is getting more difficult for me to sit for long periods of time. I do tell my students that like any other physical activity (and sitting seiza is a physical activity) you must get in shape.

Sensei once told my husband when he first began to study tea, to sit in the bathtub at home. He did, but it was so painful for him that he thought that sensei recommended it because it was almost a relief to sit on tatami after sitting on the cold porcelain! What she forgot to tell him was to fill the bath with hot water so that it would relax the muscles and tendons and help buoy up his weight.

Seriously, sitting seiza does not come naturally to us. I tell my students that they need to get into shape. Sitting once a week will only get you so far. It helps to sit a little bit every day and work up to longer and longer periods of sitting. I have my laptop computer on the coffee table and sit seiza while working on computer for as long as I can before I rest, or I sit seiza while watching TV to keep in shape. Breathing, and keeping your mind focused on your temae will also help.

Sometimes, sitting on the meditation seat helps, especially with the ankles. New students usually need a sitting aid such as this stool. One thing to be very sure of is if your feet and ankles are numb, please be very careful and not get up until you get the feeling back into your feet. We have time, and a good first guest will be able to tell a story, or discuss some aspect of the tea room, or utensils to help distract the other guests while the host recovers feeling in his legs. You can purchase one of these seats from SweetPersimmon.com. It comes in its own little carry bag that gives you a little extra padding, too.

Sometimes, sitting on the meditation seat helps, especially with the ankles. New students usually need a sitting aid such as this stool. One thing to be very sure of is if your feet and ankles are numb, please be very careful and not get up until you get the feeling back into your feet. We have time, and a good first guest will be able to tell a story, or discuss some aspect of the tea room, or utensils to help distract the other guests while the host recovers feeling in his legs. You can purchase one of these seats from SweetPersimmon.com. It comes in its own little carry bag that gives you a little extra padding, too.

Another thing that I have discovered that helps is acupuncture. In fact, if you are in Portland, I recommend Working Class Acupuncture, because they charge a sliding scale $15-35 per visit. Very affordable. It is community acupuncture. They treat you in lounge chairs in one big room. You can stay for as long as you like. You can find other community acupuncture clinics all over the U.S.

Besides the pain of sitting seiza, acupuncture will help with a lot of other things, too.

May 30, 2010

Sitting seiza for tea

May 29, 2010

Imperfect beauty

Trying to understand the wabi aesthetic of the tea ceremony is very difficult because it is difficult to quantify. One of the principles of wabi is "fukanzen no bi" or imperfect beauty.

Trying to understand the wabi aesthetic of the tea ceremony is very difficult because it is difficult to quantify. One of the principles of wabi is "fukanzen no bi" or imperfect beauty.

Most people thnnk that there is a universal kind of beauty, but each person has a different sense of beauty -- depending on our culture, education, country and upbringing. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. For example, the line from the ocean to Mt. Fuji is beautiful, but a cloud obscuring part of the line is more interesting and beautiful to some people.

The usual concept of beauty is close to perfect. Bronzes and celedon ceramics from China were of perfectly symmetrical beauty where each side matched. The tea masters in Japan thought that it was boring. They looked to Korean rice bowls -- asymmetrical, earth toned, rough textured and thought them beautiful. These bowls, with their imperfections were more human. That led Rikyu to create raku. Raku bowls, because they are not turned on the wheel, are made to fit in the hand and it doesn't conduct heat well so the hot tea in it will not burn your hand. Raku means enjoyment, ease, pleasure or happiness.

Oribe and shino ware are very popular with tea students and potters. But these are not my personal favorites because there is so much bad oribe and shino copies out there. Oribe knew just how far to push the boundaries, while copies of his work often go beyond. Students think that just because it is distorted, or rough it must be wabi and therefore beautiful. Purposeful distortions of the form, sloppy craftsmanship, or just plain ugly pieces abound. Wabi is not slobby.

Tea students must be able to differentiate between forgiving imperfection, and celebrating imperfection. Celebrating imperfection leads to weird stuff for its own sake rather than looking at the individual strength of the piece and forgiving its imperfections because of its strengths.

May 28, 2010

Tea and Music

I had an excellent comment from a reader of the blog regarding the similarities of Chado and music. It was brought more into focus for me this week when I had Gregg from Seattle visit Issoan Tea room. Gregg is the chajin who gave the April Fool's chakai. Gregg's partner is an accomplished viola gamba musician and we had a long and interesting discussion comparing chado and music.

It started with the scroll, "ichigo ichie" that was hanging in the tea room as I made tea for them. He said like chanoyu, every time you play a piece of music, it is different and that no two performances are exactly alike. He also commented that sometimes while playing everything comes together in a natural flow without conscious effort, but to get there takes years of practice and playing with other people.

I was wondering if the analogy held up between tea and music. Much of it does. The constant practice, the training, preparation, timing and working together with others, the striving to follow procedure, and allowance for creative expression within a rigid structure.

What about you? Do you think the analogy between tea and music holds up? In what ways?

May 27, 2010

Kuwa Ko-joku for Boy's day

The kuwa ko-joku (literally small mulberry wood stand) inspired Senso, the Urasenke 4th Generation tea master to build this tana from a traditional stand to hold arrows. The top and middle shelves had many holes to hold the arrows.

The kuwa ko-joku (literally small mulberry wood stand) inspired Senso, the Urasenke 4th Generation tea master to build this tana from a traditional stand to hold arrows. The top and middle shelves had many holes to hold the arrows.

In this tana, the top shelf edges were beveled into the yahazu or arrow notch shape. Senso gae this kuwa ko-joku to his brother Koshin, the 4th generation Omotesenke master and it became widely used by Omotesenke followers. It wasn't until Gengensai (11th generation Urasenke) used it that Urasenke followers began to use it.

Because of its association with archery, this tana is especially appropriate for Boys' Day (Tango no sekku, fifth day of the fifth month). You can see the kabuto or helmet futaoki is displayed on the middle shelf with the mizusashi. Because of the tall, narrow shape of this tana, a tsutsu (cylinder) shape mizusashi is preferable. The space below is for a kensui, but it must be wide and flat as you can see, to fit on the bottom shelf. Unusually, the hishaku or water ladle, is balanced upside down between the front and back posts rather than on the top shelf. Because this is a four legged tana, the mizusashi must be pulled all the way out to refill it at the end of the temae.

May 26, 2010

Just put the flowers in

Often, we have few choices for flowers in the winter, but now, there is an abundance of flowers to choose. You only need a few. Sometimes you get lucky and the arrangement comes together. For example, I was quite pleased with the arrangement this month for the Portland Japanese Garden tea demonstration.

I went out in the early morning in my neighborhood to look for flowers for the chakai. One of my neighbors has a very large azalea plant and I asked if I could clip a few. After gaining permission, I saw this cascade of a branch and brought it into the tea room to arrange.

I don't know if you can see in this photo, but the blossoms have a slightly pink tinge to the edges of the petals. The branch cascaded down below the level of the opening and the stem was rather short and the bamboo vase was perfect for it. I carefully put it in the vase to look at it. Not a single thing was done after that. No fussing, no rearranging, no clipping. The flowers and leaves were still wet from the morning rain, and the arrangement, though a little wild, had a rather innocent look to it.

The lesson here for me is to start arranging chabana before you even cut the flowers. Look and look for the flowers, and imagine what kind of vase they will sit in. Choose the flowers first and then choose the vase.

May 11, 2010

Chado Presentations

Friday May 14th, 12:30-1:30 Rock Creek PCC as part of the their Art Beat Week, I will be presenting Tea. The first 15 people to come will receive a sweet and a bowl of tea. Free and open to the public.

Saturday, May 15th, The Portland Japanese Garden will sponsor a public tea demonstration at 1 and 2 pm at the Kashintei tea house. This is a demonstration only. Free with Garden admission.

May 9, 2010

Tea utensils that will last 400 years

There are many examples of tea utensils from the 16th century and earlier because they were so well taken care of. Tea utensils were made to be used rather than put away in the closet, never to see the light of day. So get out your tea utensils (dogu) and use them, but take care of them as if you want them to last 400 years.

There are many examples of tea utensils from the 16th century and earlier because they were so well taken care of. Tea utensils were made to be used rather than put away in the closet, never to see the light of day. So get out your tea utensils (dogu) and use them, but take care of them as if you want them to last 400 years.

I remember my sensei teaching me how to care for the iron kettle after class, how to wash and dry teabowls, and care for lacquer with gloves. There is a certain way to tie the boxes that dogu come in so that you can stack them. Paying attention to detail with thoughtfulness and carefulness shows respect for the dogu, but also for yourself. The attention to detail in taking care of your dogu shows more about your character and state of mind than how perfect your temae is.

Taking care of your dogu doesn't just apply to tea utensils, it is how you treat everything in your life. Like the famous baseball player Ichiro:

The man whose first name has come to symbolize greatness in hitting might also be the most meticulous player when it comes to caring for the tools of his trade. He rubs the soles of his feet every day with a rounded wooden stick. He cleans his own spikes and glove after games. And he prefers to carry his own bats, which are cut from Japanese ash wood called aodamo and custom made from specs chosen by Ichiro on a tour of the Mizuno factory in Japan in 1992. "I've never seen anybody that I've played with take care of their equipment with just carefulness, thoughtfulness. Most guys throw their gloves around. Not him," he said. "He told me that when he cleans his glove up after the game, that means he's already thought about the game that day and while he's wiping it off he is wiping off the game that day."

Want more detailed information on how to care for your tea utensils? Here's a post written by Gary-sensei.

May 5, 2010

Okeiko guidelines

For every class:

- Remove shoes and put on white socks. Put your shoes away neatly in the shoe cupboard or line them up under the shoe bench.

- Store your bags and other things in the place provided.

- Use tsukubai or wash hands first. Bring your own handkerchief to wipe your hands.

- Always bring your fukusabasami with fukusa, fan, and kaishi.

- When entering the tea room, enter on your knees unless carrying something.

- Always look at the scroll and the flower arrangement when entering the tea room for the first time.

- Sit quietly until the sensei enters the room.

- All classes start and end with aisatsu

During class time:

- Always clean up after yourself. Wash your bowl, chakin, whisk, and put away. Help with clean up after class and to do the mizuya work, unless the mizuya cho dismisses you.

- The mizuya cho is in charge of the mizuya. You will follow instructions without argument. If there is a dispute, call a meeting with the cho after class.

- Watch senior students and learn from them; from temae to tea room behavior to clean up chores. If you don’t know how to do something, ASK.

- Never pass any tea utensils hand to hand. Put it down in front of the other person and let them pick it up.

- Don’t take notes in the tea room. Wait until after you leave the room to write anything down. Train your mind to remember.

- Wait until an appropriate time to ask questions. Distracting the teacher takes away from fellow students teaching and you would want the sensei’s attention on you for your lesson.

- No teaching commentary from the side. There is only one teacher in the room. Respect the sensei to teach what is necessary.

- Sitting seiza can be painful. Ask for a cushion, or stool. Changing position is helpful, but don’t make a production of it. Don’t get up and walk if your feet are numb.

- Try not to call too much attention to yourself in the tea room. The sensei notices everything.

- Working together is necessary for tea to work. Cooperation is valued.

- Read, research, look things up on your own. There is the library and books and the internet. You are in charge of your learning and it is not up to the teacher to make sure you progress.

- Everyone is your teacher. You can learn something from everybody.

Training in chado is hard and we must study and train diligently. It is also a good reminder for me.

May 4, 2010

Kimono magic

For those of you who have questions about kimono and dressing, she may be more knowledgeable than I am about the fine points, work arounds, and tips and tricks. Especially about kimono that is not for chanoyu.

She's new to blogging. Please follow the link and welcome her with your comments.

May 3, 2010

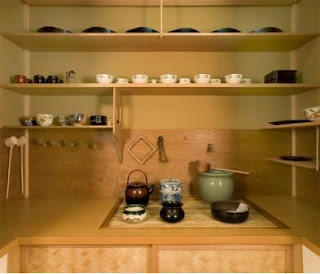

Where do things go in the mizuya?

The general rule should be that when there are several utensils of the same kind, the most formal is placed to the rear, the next is placed in front of it and the third the rear of the next row.

As you can see from the diagram, starting from the bottom row, are the kensui. the next row on the bottom of the mizuya from the left are the hishaku, the most formal at the back. Then the chasen are hung from the back wall; the most formal, smoked bamboo on the far left.

The bent wood mizusashi is the most formal a the back , with the less formal in front of it. The ceramic mizutsugi at the back with the metal one in front of it. Hanging on the wall next is the wooden square for placing the kama on it and the kama brush. Below is the shallow water pan (chakin darai) with chakin and sweets picks. Next is the large water jar and hanging to the right are the filter ladle and large water ladle.

The next shelf up are teabowls in order of formailty: black raku, red raku, Hagi, and others appropriate to koicha, bowls without decoration, and those with decoration. Next are futaoki: metal, ceramic, bamboo.

The next shelf up: chaire in order: karamono, Japanese katatsuki, other Japanese type, and wide Japanese type and then others. Usuki (thin tea containers): black laquer chu natsume, decorated chu natsume, hira natsume, other lacquered, ceramic thin tea containers and others. Tea scoops: ivory, bamboo with no node, bamboo with node at the bottom, bamboo with node in the middle. Next lacquer mizusashi lids, and kettle lids on futaoki. On this shelf is the appropriate place for several clean towels for drying utensils. The towel for hands usually hangs from a peg on the right side of the mizuya. On the floor there should be a floor towel.

On the next shelf are temmoku tea bowls: on lacquer stands and on plain wood. An tray for incense appreciation then kogo. Next to that is an orisue for kagetsu, and wood boards for kinin kyotsugu. The next box is a satsubako, with the otsubukuro bag on top and next the box with tools for measuring tea.

On the top shelf from the left are the charcoal stand with flower stand on top, charcoal basket and ash bowl. Next are the folded paper kama kamashiki on top of the woven reed one with the kan in front. The ash spoon, feather brush and fire tongs for sumi and two large ceramic bowls for charcoal ceremonies. Finally at top right is the metal pot for carrying burning charcoal.

While this diagram deals with a very large well-equipped mizuya, the principles should remain the same whatever the situation. Sometimes the mizuya has fewer shelves and the tea containers and teabowls are on the same shelf. In such cases, the most formal tea container is a the rear left and most formal teabowl is at the rear right.

May 2, 2010

Poetry and Tea

Citing many famous tea masters and their poetry, Maggie deftly weaves the two disciplines of Chado and Renga together in their principles and aesthetics. In fact, many tea masters were accomplished poets.

Please go check it out and welcome her on her blog with your comments.

May 1, 2010

Mizuya Guidelines

In the preparation room silence is the rule. Idle chatter is distracting. Clean utensils immediately and maintain the mizuya in a state of readiness. Never leave personal items in the mizuya. At the end of class, ready utensils for the next day’s activities.

And Sensei says: the mizuya should be kept clean and orderly at all times. No excuses.

Often the preparation room is a small confined space that people need to share and work efficiently in. The tea house in Seattle has a small, sit down mizuya that is only one mat (3 feet by six feet). If everyone is working together and efficient, then 3 people can work in this space and produce a hundred bowls of tea.

Often the preparation room is a small confined space that people need to share and work efficiently in. The tea house in Seattle has a small, sit down mizuya that is only one mat (3 feet by six feet). If everyone is working together and efficient, then 3 people can work in this space and produce a hundred bowls of tea.It is very tempting to hang out in the mizuya because that is where a lot of the action is before and after class. But loiterers get in the way and working around someone who just chatting interrupts the work flow and is distracting. I don't know how many times I have been kicked out of the mizuya by the cho (head of the mizuya) for chatting more than working. My sempai once told me that if he didn't see my hands working more than my mouth I was to take myself out until I could control myself.

When I was the cho, I myself have kicked people out of the mizuya. If you are not working, get out of the mizuya. It is a place to work, not socialize.

If you first come to class and see that there are things to be cleaned, just do it. It doesn't matter if you made the mess or if it someone else's responsibility. If you see it, it is assumed that YOU are responsible. Clean it up immediately.

After your lesson, you MUST clean up all of your utensils immediately after the aisatsu (thanking the sensei for the lesson). Rinse your bowl and put away, clean your chasen, rinse all the tea off your chakin. Clean the stickiness off any sweets tray, wipe the chashaku with a tissue, and refill the natsume for the next student. Put away all of your utensils in their proper places.

When class is finished, everyone helps to clean up. If there is no cho assigned, the most experienced student becomes the cho and must ensure that all of the cleaning is done properly, and utensils put in their proper place. If there are less experienced students hanging about not knowing what to do, it is your responsibility to show them the proper way to clean, prepare and work in the mizuya. Notice I said show them, not tell them.

" In the preparation room off the Totsutotsusai tea room at Urasenke in Kyoto there hangs a plaque in the hand of the thirteenth generation Grand Tea Master, Ennosai, listing the rules for the mizuya. In addition to a chart showing the storage places for the utensils, there is written: 'This is a training ground for the tea room . Recently it has not been kept in order and has become quite unsightly. I have drawn a chart; henceforth, people who finish practicing must place all utensils back where they found them.' Precisely because the preparation room is not seen by the guests, it must be kept cleaner than the tea room itself." ~ from The Spririt of Tea by Sen Soshitsu XV.

" In the preparation room off the Totsutotsusai tea room at Urasenke in Kyoto there hangs a plaque in the hand of the thirteenth generation Grand Tea Master, Ennosai, listing the rules for the mizuya. In addition to a chart showing the storage places for the utensils, there is written: 'This is a training ground for the tea room . Recently it has not been kept in order and has become quite unsightly. I have drawn a chart; henceforth, people who finish practicing must place all utensils back where they found them.' Precisely because the preparation room is not seen by the guests, it must be kept cleaner than the tea room itself." ~ from The Spririt of Tea by Sen Soshitsu XV.